- Home

- Dermot Milligan

The Donut Diaries

The Donut Diaries Read online

Contents

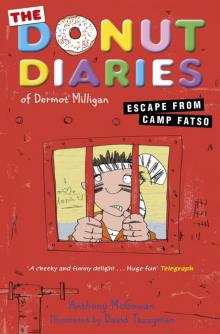

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Friday 30 March

Saturday 31 March

Saturday 31 March

Sunday 1 April

Monday 2 April

Monday 2 April

Tuesday 3 April

Wednesday 4 April

Thursday 5 April

Friday 6 April

Sunday 8 April

Monday 9 April

Tuesday 10 April

Wednesday 11 April

Thursday 12 April

Friday 13 April

Saturday 14 April

About the Author

Also by Anthony McGowan

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Book

I’m Dermot Milligan, also known to friends and foes alike as Donut.

It’s finally happened. I’m being sent to the most evil place in the world: CAMP FATSO.

And it’s worse than I imagined. I sleep in a hut with five other PRISONERS. We’re fed on a diet of GRUEL and CARROTS. We’re controlled by the terrifying BOSS SKINNER and his guards. And there are no DONUTS anywhere.

But Camp Fatso is hiding a secret – and I’m going to find out what it is. And with the help of my gang, and some old friends, I’m going to ESCAPE . . .

To the illustrative genius of David Tazzyman;

and to Andy Stanton, who raised the bar,

leaped it, and then made rude gestures

from the far side to try to put me off.

Friday 30 March

‘CHEER UP, DONUT,’ said Renfrew, a happy smile on his goofy face.

Normally he looked a lot like a vole, but today, for some reason, I thought he had moved more in the direction of squirrel.

Or possibly gerbil.

‘No,’ I replied.

We were walking towards the school gates on our way home. It was the last day of term, and the two-week-long Easter holiday lay ahead.

THE LAST DAY OF TERM!!!!!

Throughout history, human kids have marked the end of term with grand celebrations. In the Stone Age they would paint themselves blue and dance naked around a roasting mammoth. The Romans used to hold massive end-of-term gladiatorial contests, where the guy with a net and a trident and a really short skirt would fight some other guy with less cool but probably more efficient weapons and a slightly longer skirt, while the kids yelled encouragement and feasted on larks’ tongues and fried bats. In the Middle Ages, nerdy children would clutch ribbons and skip around a giant stick while the cool kids jeered and hurled rocks at them.

Yes, it should have been a great day.

So how come I looked like someone who’d had all the jam sucked out of his last donut, to be replaced by some other disgusting slop, such as monkey poo or cat sick?

The answer lay in two words. Two fatal, deadly, foul, evil, putrid, stinking words.

CAMP. FATSO.1

‘It’s your own fault, really,’ said Spam, my second best friend.

If Renfrew, my first best friend, was a vole (or squirrel or gerbil), then Spam was a stick insect that had been zapped up to giant size in a freak nuclear accident.

It was true.

It was my fault.

I hate it when things are my fault. It takes all the fun out of grumbling. But there it was, pointing at me, the Obese Finger of Truth. I couldn’t avoid the fact that I had sort of semi-volunteered to go to Camp Fatso.

This was as a result of a) a really, really complicated story that would take me another whole diary to explain,2 and b) realizing that I was, in fact, a little too plump, on account of my donut addiction, and could actually do with a bit of slimming down.

And so I responded to Spam’s statement in time-honoured fashion: by hitting him with my school bag and calling him a stupid lanky streak of camel pee.

Even without the looming horror of Camp Fatso it had been quite a traumatic last day of term. Nothing bad happened for the first half of it, if you exclude the fact that the last school dinner was some sort of pie that should have been standing trial at the International War Crimes court in The Hague. So obscurely disgusting was this pie that not even the dinner ladies could tell us what sort of pie it was. Spam hazarded a guess at hedgehog. Personally, I thought it might have been whale and bacon.

Either way, it was no sort of preparation for the absolute and utter final last lesson of term, which was PE. I suppose I should have had an inkling of what was coming. Mr Fricker, our deeply demented PE teacher, was famous for two things:

1. The variety of screw-on mechanical contraptions which appeared in place of actual human hands;

2. His last-day-of-term football matches, which often had a casualty list exceeded only by a few famous battles, such as the Somme and Stalingrad.

And so, for the last lesson of term, Mr Fricker warmed us up by shouting at us for a while about personal hygiene (one of his obsessions), going into embarrassing detail about which parts of our bodies we should wash most thoroughly, and which bits shouldn’t be washed at all, except under qualified medical supervision.

And then it was out onto the field for a classic David vs Goliath contest, with my form, Burton (David), taking on the might of Xavier (Goliath).

Just to explain, our school has four forms: Burton, which has all the duffers, fatties and weirdos; Campion, which is for the brainiacs; Newman, which is for the sporty-but-thick types; and Xavier, which has the kids who are good at everything, except being decent human beings.

We have PE lessons with Xavier, about half of whom are in the school football team, including my mortal enemy, the Floppy-Haired Kid.3

No one from Burton is in any of the school teams, not even for games like ping-pong and badminton, designed for people who aren’t very sporty or co-ordinated. Most of us are useless, although my friend Corky is quite dangerous. I don’t mean dangerous as in a dangerous striker who might inflict damage on the opposing defence. I mean dangerous in that he might well crash into you at high speed, and then try to chew your knee-caps off.

Renfrew and Spam, needless to say, were so incompetent that if you watched them in isolation you just couldn’t guess what sport they were playing. Instead of football it could easily be golf, or even the ancient Icelandic pastime of Falling Over For No Good Reason At All.

I was actually one of our better players, which tells you all you need to know.

‘And to add a bit of spice to the occasion,’ Mr Fricker decreed in one of his less shouty voices (although by any normal standards he was screaming), ‘the losers will clean the boots of the winners. And,’ he added, ‘I’ll even things up by playing for the Xaviers.’

‘But we’ve already got eleven, sir,’ said Justyn Bragg, who hadn’t quite got it yet.

‘I’m afraid you’re injured,’ said Fricker, his stare suddenly as cold as a nudist on a glacier drinking a glass of liquid nitrogen.

‘But I’m not injured,’ said Justyn, still not getting it.

‘Not injured yet,’ said Fricker, screwing in his football hands, which were basically the same as his punching-a-rabbit-to-death hands, at which point Bragg got it, and started limping extravagantly.

Outside, the rain had begun to turn into sleet, as it usually did for outdoor PE. The pitch was made up almost exclusively of mud and puddles. I saw a solitary blade of grass, standing there like the sole survivor of some terrible disaster that had wiped out all other plant life from the earth.

‘This is going to be fun,’ said Renfrew.

‘No, it isn’t,’ said Spam, who had a way of missing sarcasm, even when it reached up and slapped him in the face. ‘I think it’s going to be really unpleasant.’

And how right he was.

We Burtons were playing into the wind in the first half, and most of the team huddled together like sheep, while the Xaviers streamed through us like the marauding Mongol warriors of Genghis Khan.

I’m sure I don’t need to tell you who played the part of Genghis.

Mr Fricker was all over the pitch, yelling out commands, screaming for the ball, crunching into tackles, chopping down his enemies with his mighty sword. Well, not the sword part. But anyone who got in his way would end up face-down in the mud, with the imprint of Fricker’s football studs on the back of his neck.

By this stage the girls had finished their netball match and had come over to watch us. This added greatly to the embarrassment. The basic rule in life is that when you’re being humiliated it’s best not to also have a load of girls laughing at you and yelling out, ‘Hey, fatty, shift yourself, we can’t see what’s happening!’ and, ‘He doesn’t know where he’s going, he needs a fat-nav!’ and that sort of thing.

I particularly didn’t like being watched by the girl known as Tamara Bello (because that was her name), who didn’t bother yelling insults, but just looked vaguely bored by it all, as if she’d rather be reading her book of short stories by Chekhov, a Russian author who died in prison, where he’d been sent for murdering millions of people by boredom.

And then, on the field, farce turned to tragedy, as it so often does. Or maybe this was more tragedy turning to farce. No, actually, this was farce turning into even bigger farce.

We were six–nil down. The Floppy-Haired Kid had scored two goals, and Fricker had smashed in the other four. We were just generally praying for it all to be over so that we could get down to cleaning the boots of the sneering Xaviers, and then going home to lick our wounds, eat our donuts, etc., etc.

Then the FHK got the ball and went for his hat trick. I tried to tackle him, but he dribbled round me, stopped, ran back and dribbled round me again, smirking all the time. I got rather annoyed about that, as it was adding insult to injury, and adding insult to injury is pretty bad, being beaten for unpleasantness only by adding another injury to the first injury.

So I was a bit riled. I chased after the FHK as best I could. I wouldn’t normally have much chance of catching him, but I had a lucky break – the ball hit a giant puddle and floated away, out of his control. Suddenly there were a load of us splashing around in there like, oh, I don’t know, otters or seals or something, which was quite good fun.

The FHK was enjoying it rather less than the rest of us because he didn’t like getting dirty or having his hair messed up, so he tried to deliver one of his sly and nasty kicks in the general direction of my rear end, but he only succeeded in slipping and getting a mouthful of muddy water.

The ball broke loose, and I was the one nearest to it. Most of the players were caught up in the massive puddle-splashing fight, and I realized that I had a chance to trundle up the pitch and score a consolation goal.

Mr Fricker, however, had other ideas. Consolation goals were not part of his world view. He believed that you haven’t really beaten your opponent until you’ve ground him into the dirt. ‘The point,’ he said to us once, ‘is not to defeat the opposition, but to DESTROY IT.’

So as I ran with the ball up towards the other end of the pitch, with the girls laughing at my chubby white legs and my own team more interested in the mud fight, I sensed the oncoming approach of the insane PE teacher. His fist-shaped football hands were pumping up and down like the pistons of a nightmare express train powered by rocket fuel and high-octane fart gas.

He could probably have just tackled me, but he wanted more than that. He wanted to get across the message that nobody scores against the Fricker. In fact, nobody should even try.

So he launched himself into one of his infamous sliding tackles, otherwise known as ‘the Scythe’, the purpose of which is to crunch through your legs like a hatchet through dry sticks. I prepared for the agony, expecting to spend some time flying through the air before landing on my head. There was a small chance that Fricker’s tackle would actually kill me, and I imagined all the nice things people would say about me at my funeral service, although it was sort of ruined by the presence of Ruby and Ella, my horrible sisters, who didn’t take it seriously at all and laughed and chewed gum through the whole thing and turned it into a Fiasco.

But death for Dermot did not result, on this occasion. Mr Fricker began the sliding part of the tackle. He was about ten metres away when he initiated the Scythe. To begin with it all went well. Fricker was horizontal, and heading straight for my legs, cutting through the mud and surface water like a powerboat. I saw the metal of his football studs gleaming – the rumour was that he sharpened them to improve their grip and cutting edge. They were like the slashing claws on the back legs of a velociraptor.

I seriously considered screaming, but decided against it because of Tamara Bello. The same went for wetting my pants. I didn’t know much about girls, but I did know that screaming and pant-wetting are quite far down the list of ways to impress them, coming just above bad breath and just below following through after a wet fart.

And then I noticed the look on Fricker’s face. At the beginning of his slide it had been his standard, steely, children-slaughtering look. And then it changed, first to a look of mild surprise, then horror, and finally agony. He was still sliding, but his speed was slowing. I realized that he wasn’t actually going to reach me. The whole thing had been initiated too early, so desperate was Fricker to chop my legs off before I had the chance to score. But I still couldn’t quite work out why his face was purple and his eyes were crossed.

Finally he came to a complete stop. There was the PE teacher, lying on his back in the mud, staring up at the sky and emitting the sort of sound you’d expect from a wounded bat.

‘You OK, sir?’ I said, walking towards him tentatively. Approaching injured PE teachers is one of those things, like going back to a lit firework you think has gone out, or plucking a bum hair from a sleeping buffalo, that is definitely not recommended.

A few other kids had come up by now.

‘His shorts,’ said someone. ‘Look at his shorts.’

Generally, most of us tried to avoid looking at Mr Fricker’s shorts, but once my gaze was directed there I understood immediately what had happened. Mr Fricker’s long slide had resulted in his shorts getting rammed right up his . . . I mean into his . . .Well, let’s just say that he’d given himself the mother of all wedgies. And now he was clawing at the shorts with his artificial hands. But the trouble was that, as I’ve said, he had his punching hands on, which were clearly totally useless at pulling shorts out of bum cracks. It was kind of tragic. Someone behind me said something in a low voice, and someone else spluttered. I looked around. I saw the smirking face of the FHK. He was enjoying the spectacle. Up until then, something inside me, something horrible and mean-spirited, had been enjoying it too. But I realized that anything that amused the FHK couldn’t really be funny.

‘We can’t leave him like this,’ said Renfrew, who was now at my side, as he usually was at times of crisis.

‘What can we do?’ I said.

‘You’re going to have to go in,’ said Spam, looming up on my other flank, as he also usually did when I needed him, or when we were just hanging out, getting chips, sitting on walls, etc., etc.

‘Why me?’ I asked, but only in the way every hero at some point or other in the story tries to Escape His Destiny. I already knew the answer. It was because I was standing a bit closer to Fricker than everyone else, and so it was, by the iron laws of schoolboy logic, up to me.

I nodded.

‘OK, Renfrew, give me your sock.’

‘My sock?’

‘Just get on with it, man, there’s no time to lose.’

‘B-but—’

‘NOW!’

Fricker had now gone from purple to white. Blood circulation had clearly been impeded, if not cut off altogether.

I

held out my hand, and Renfrew laid a muddy sock in it. I kneeled beside the PE teacher.

‘Can you hear me, sir?’ I said.

Fricker blinked a couple of times. I think his sight may have gone. A dry tongue flicked at his lips.

‘I’m going to try to yank them out, sir. The shorts, I mean. It’s going to hurt. You should bite on this.’

I put Renfrew’s sock between the parched lips, and Fricker clamped down on it. And then, amid the horrified groans of the crowd, which now included the girls and their netball teacher, Miss Gunasekara, I heaved at the small amount of short fabric that was still visible. Mr Fricker became utterly rigid, as if he’d been given an electric shock. To begin with there was no movement from the shorts: they were so embedded I thought only dynamite would extract them. Then I felt a tiny tremor. They were shifting! But it was all proving too much for me. I was already worn out from the football. Sweat poured into my eyes. My muscles shook and I could feel the cold talons of cramp begin to pierce my biceps.

Fricker was staring at me now, although I don’t know what he was actually seeing. Perhaps rather than the overweight kid before him, he saw the gates of heaven, or an open football goal, or the mother and father who’d abandoned him as a child.4

Anyway, he was losing his grip on life, as I was losing my grip on his shorts. And then I felt a pair of immensely powerful hands close around mine, and smelled, at the same moment, a strong whiff of horse meat.

It was Ludmilla Pfumpf, the strongest and most fearsome human being in our year.5

Together we made one last, supreme effort, and with a noise like the roar of a military jet passing over our heads, Mr Fricker’s shorts were torn from his bottom.

Immediately, Miss Gunasekara, who’d been paralysed by fear or fascination throughout the whole operation, went into action. She took a netball bib from one of the girls and covered Mr Fricker’s shame, and then yelled at us all to go back to the gym and get changed.

None of the kids thanked me for rescuing Fricker, and in fact most of them, led by the FHK, called me various names, the mildest of which was teacher’s pet. It wasn’t surprising, really. He was a dangerous lunatic, and we’d all have been safer if he’d been permanently disabled by the Epic Wedgie.

The Donut Diaries

The Donut Diaries